SOLID principles in JavaScript

In this blog post, we will explore each of the SOLID principles with JavaScript examples using function () constructor and prototype methods. You can consider these as class and class methods respectively.

What is the SOLID principle? #

- SOLID is an acronym for five principles of object-oriented programming (OOP) and design.

- Guiding principles to write maintainable, scalable, reliable, efficient, stable, testable and clean code.

- Even though these principles are related to OOP, we can apply these principles to other programming paradigms as well.

Let's explore each of these principles with JavaScript examples. Imagine we are building a patient management system for a hospital. To begin with, we can create the following classes to model our system.

function Hospital() {}function Patient() {}1. Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) #

"A class should have only one reason to change."

Before applying SRP #

function Hospital() {

this.patients = [];

}

// add patient to the hospital

Hospital.prototype.addPatient = function (patient) {};

// remove patient from the hospital

Hospital.prototype.removePatient = function (patient) {};

// get all patients from the hospital

Hospital.prototype.getPatients = function () {};

// export patient data in default PDF format

Hospital.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {};

// notify patient via default EMAIL channel

Hospital.prototype.sendPatientNotification = function (patient) {};One can argue that all methods defined in the above class are related to the functionality of Hospital. But these functions are not cohesive and focused, so they have many reasons to change.

- What will happen if the hospital decides to change the format of the exported patient names? (Think about changing the format from PDF to CSV)

- What will happen if the hospital decides to change the way it notifies the patient? (Think about changing the notification channel from EMAIL to SMS)

Wouldn't it be nice if we could separate these responsibilities into different classes?

After applying SRP #

function Hospital() {}

Hospital.prototype.addPatient = function (patient) {};

Hospital.prototype.removePatient = function (patient) {};

Hospital.prototype.getPatients = function () {};

function DataExporter() {}

DataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {};

function Notifier() {}

Notifier.prototype.sendPatientNotification = function (patient) {};I hope we have achieved a better separation of concerns by separating the responsibilities into different classes: Hospital, DataExporter and Notifier. Now, each of these classes have a single reason to change and minimize the effects of change.

With the above changes,

Hospitalclass has only one reason to change, which is to add or remove patients.DataExporterclass has only one reason to change, which is to export patient data.Notifierclass has only one reason to change, which is to notify patients.

2. Open-Closed Principle (OCP) #

"Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification."

Before we dive into examples, let's first understand some patterns that help to extend our application.

What are the ways of extension? #

- Inheritance: It is one of the ways to achieve extension. But since subclasses are tightly coupled to its parent class, users need to know the internal implementation details of the parent class. So, this is not considered ideal for extension.

function CsvDataExporter() {}

Object.setPrototypeOf(CsvDataExporter.prototype, DataExporter.prototype);

// override parent exportPatientData method to export patient data in CSV format

CsvDataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {};

function XmlDataExporter() {}

Object.setPrototypeOf(XmlDataExporter.prototype, DataExporter.prototype);

// override parent exportPatientData method to export patient data in XML format

XmlDataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {};- Configuration: With this approach, users should not need to know the internal implementation details of the parent class. Instead, they can configure the class with the configuration object to achieve extension.

function DataExporter(config) {

// let's assume config object has a exportPatientData method

this.config = config;

}

DataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {

return this.config.exportPatientData

? this.config.exportPatientData(patient)

: this.defaultExportPatientData(patient);

};

// export patient data in some default format

DataExporter.prototype.defaultExportPatientData = function (patient) {};

// create instances

const csvDataExporter = new DataExporter({

exportPatientData(patient) {

// export patient data in CSV format

// CSV specific logic goes here

},

});

const xmlDataExporter = new DataExporter({

exportPatientData(patient) {

// export patient data in XML format

// XML specific logic goes here

},

});Now, imagine a situation where we need to add a new feature to support CSV and XML data download for patients.

Before applying OCP #

function Hospital() {}

Hospital.prototype.downloadPatientDataAllFormats = function (patient) {

// existing data format logic goes here ....

// new code to support CSV format

const csvDataExporter = new CsvDataExporter();

csvDataExporter.exportPatientData(patient);

// new code to support XML format

const xmlDataExporter = new XmlDataExporter();

xmlDataExporter.exportPatientData(patient);

};

const hospital = new Hospital();

const patient = new Patient();

hospital.downloadPatientDataAllFormats(patient);What will happen if we need to export data in different formats in the future again? #

- We need to modify

downloadPatientDataAllFormatsmethod to support the new data format. Correct? - This violates OCP. We are modifying the existing code to support the new feature.

After applying OCP #

function Hospital() {

this.patientDataExporters = [];

}

Hospital.prototype.registerPatientDataExporter = function (exporter) {

this.patientDataExporters.push(exporter);

};

Hospital.prototype.downloadPatientDataAllFormats = function (patient) {

for (const exporter of this.patientDataExporters) {

exporter.exportPatientData(patient);

}

};

const hospital = new Hospital();

// csvDataExporter and xmlDataExporter are instances of DataExporter class

hospital.registerPatientDataExporter(csvDataExporter);

hospital.registerPatientDataExporter(xmlDataExporter);

const patient = new Patient();

hospital.downloadPatientDataAllFormats(patient);- With the above changes, we have achieved the extension without modifying the existing code.

- If there is a new requirement to support a new data format, we can just create an instance of the new data exporter type and register it with the

Hospitalclass from outside of theHospitalclass.

Can we predict everything about the future and design the class/abstraction? #

- Answer is no.

- It is not possible to foresee all future use cases. We might think about a large configuration object to handle all the future use cases. But it is not a good idea because it involves both cost and complexity.

- There should be a balance between possible future use cases and a focused abstraction that has some boundary or constraints.

- We can think about involving customers from the beginning to get feedback on the future use cases of the system that is being built so that we can design the abstraction accordingly. But again, it is not possible to predict everything about the future.

3. Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) / Behavioral Subtyping #

"Subtype should behave like Supertype"

Let's introduce a DataExporter class based on the patient's age and some config. We are only exporting patient data if the patient age is within the defined range.

// patient class

function Patient(age, nationality) {

this.age = age;

this.nationality = nationality;

}

// config class

function Config(minAge, maxAge, nationality) {

this.minAge = minAge;

this.maxAge = maxAge;

this.nationality = nationality;

}function DataExporter(config) {

this.config = config;

}

DataExporter.prototype.isAllowed = function (patient) {

// only export patient data if the patient age is within the defined range

return patient.age > this.config.minAge && patient.age < this.config.maxAge;

};

DataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {

if (this.isAllowed(patient)) {

// export logic goes here

}

};

const config = new Config(18, 60, "CANADA");

const patient = new Patient(20, "CANADA");

const dataExporter = new DataExporter(config);

dataExporter.exportPatientData(patient);Now, let's imagine we want to export patient data based on the patient nationality. We may extend the DataExporter class to support this new feature by simply changing the isAllowed method shown as below:

function NationalityDataExporter(config) {

DataExporter.call(this, config);

}

Object.setPrototypeOf(

NationalityDataExporter.prototype,

DataExporter.prototype

);

NationalityDataExporter.prototype.isAllowed = function (patient) {

// only export patient data if the patient nationality matches

if (patient.nationality && config.nationality) {

return patient.nationality === this.config.nationality;

}

return false;

};

NationalityDataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {

if (this.isAllowed(patient)) {

// export logic goes here

}

};

const canadaDataExporter = new NationalityDataExporter(config);

canadaDataExporter.exportPatientData(patient);But with this change, the derived class, NationalityDataExporter, is not semantically equivalent to its base class DataExporter.

This completely changes the semantics of the base class.

"Liskov's notion of a behavioural subtype defines a notion of substitutability for objects; that is, if S is a subtype of T, then objects of type T in a program may be replaced with objects of type S without altering any of the desirable properties of that program (e.g. correctness)." - Wikipedia

In our example, let's assume T is DataExporter class and S is NationalityDataExporter class.

- S is a subtype of T.

- We cannot replace objects of type T with objects of type S. If we do that, the results would be unpredictable, since the consuming client assumes that a

DataExporterclass works on patient age, not on patient nationality. - Objects of T are not substitutable with objects of S.

NationalityDataExporteris not a behaviour subtype ofDataExporter. This violates behavioral subtyping.

Lastly, this principle applies only if you are dealing with inheritance.

4. Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) #

"No client should be forced to depend on methods that it does not use."

- Imagine the hospital administration is considering exporting doctor's data.

- But they want to export doctor's data only in CSV format and not in XML format.

- So, let's add a new method on the

DataExporterwhich will be used to export doctor's data. Let's call this method asexportDoctorData.

Before applying ISP #

function DataExporter() {}

DataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {};

// newly added method

DataExporter.prototype.exportDoctorData = function (doctor) {};What are the implications of the above changes? #

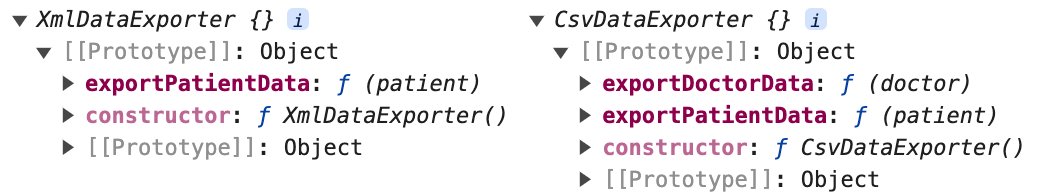

Both CsvDataExporter and XmlDataExporter classes will inherit exportDoctorData method by default. But XmlDataExporter class should not be exposed to doctor data as per the business requirement. This results in forcing unnecessary dependencies and creates confusion and maintenance issues.

How to solve this problem? #

We can use mixins to solve this problem. Mixin is a great way to add functionality to a class without using inheritance.

In the following example, we have created two mixins called PatientInterface and DoctorInterface.

After applying ISP #

// mixins

function PatientInterface() {

return {

exportPatientData(patient) {},

};

}

function DoctorInterface() {

return {

exportDoctorData(doctor) {},

};

}

// XML data exporter

function XmlDataExporter() {}

Object.assign(XmlDataExporter.prototype, PatientInterface());

XmlDataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {};

// CSV data exporter

function CsvDataExporter() {}

Object.assign(CsvDataExporter.prototype, PatientInterface(), DoctorInterface());

CsvDataExporter.prototype.exportPatientData = function (patient) {};

CsvDataExporter.prototype.exportDoctorData = function (doctor) {};

const xmlDataExporter = new XmlDataExporter();

const csvDataExporter = new CsvDataExporter();With the above changes, XmlDataExporter class is not inheriting exportDoctorData method by default.

5. Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) #

"High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions (that is, interfaces)."

Before applying DIP #

function Hospital() {

this.patients = [];

}

Hospital.prototype.getPatients = function () {

return this.patients;

};

Hospital.prototype.sendNotificationToAllPatients = function () {

const patients = this.getPatients();

patients.forEach((patient) => {

const notifier = new Notifier();

notifier.sendPatientNotification(patient);

});

};- Let's add a new method called

sendNotificationToAllPatientsto theHospitalclass. - In the above example, the

Hospitalclass is tightly coupled withNotifierclass. - When I say tightly coupled, I mean we are instantiating the

Notifierclass inside theHospitalclass inside the body ofsendNotificationToAllPatientsusingnew Notifier (). - Let's imagine

Notifierclass added some dependencies in itsconstructorto add new features. In that case, we also need to change theHospitalclass since it needs to provide those dependencies to theNotifierclass. - Internal implementation details of the

Notifierclass are exposed to theHospitalclass. This also means theHospitalclass is dependent on the implementation details of theNotifierclass.

After applying DIP #

function Hospital(notifier) {

this.notifier = notifier;

}

Hospital.prototype.getPatients = function () {

return this.patients;

};

Hospital.prototype.sendNotificationToAllPatients = function () {

const patients = this.getPatients();

patients.forEach((patient) => {

this.notifier.sendPatientNotification(patient);

});

};

// moved out the Notifier dependency from the Hospital class

// inject the Notifier instance through the constructor (Dependency Injection)

const hospital = new Hospital(new Notifier());- In the above example, we moved out

new Notifier ()from theHospitalclass and injected the instance ofNotifierclass as a dependency through theconstructorof theHospitalclass from outside of it. - This has made

Hospitalclass loosely coupled withNotifierclass.Hospitalclass is not dependent on the implementation details ofNotifierclass anymore. Hospitalclass just needs to know that it can call thesendPatientNotificationmethod on theNotifierinstance. This is the very minimal information that theHospitalclass needs to know about theNotifierclass.- So, both

HospitalandNotifierclasses are dependent on an abstraction which has a single method calledsendPatientNotification. - In javaScript, we don't have interfaces to represent abstractions. So, we can add if/else checks to only call the

sendPatientNotificationmethod if it is available on theNotifierinstance and assume this instance is the correct behavioral instance (Duck Typing).

Summary #

In this blog post, we learned about the SOLID principles in JavaScript. We explored each principle with relevant examples. If you have any questions or feedback, please let me know in the comment section below.

References

- Mastering JavaScript Object-Oriented Programming: Andrea Chiarelli